I came across a Newsweek article with a headline that read, “How Bad Is the U.S. Health Care System? Among High-Income Nations, It Is the Worst, Study Says.” Is the headline sensationalistic clickbait, or do we really have the highest-cost healthcare system and the lowest-quality system?

Upon first glance, one might believe this headline means we have the worst doctors, hospitals, nurses, technology, and training in the world. Is this what Newsweek was saying, and how is “the worst” measured?

Short Life Expectancy

Individuals born in the U.S. have a shorter life expectancy than individuals born on the same day in other economically developed countries — ouch! This harsh fact is inescapable, but does it necessarily mean we should blame terrible doctors and hospitals?

Measuring the quality of a healthcare system and the health of the population it serves is a monumental task. Life expectancy is a common measure, but that is impacted by many factors, with the quality of the healthcare system being only one.

Can you really blame the healthcare system for social and lifestyle choices that impact this number? As an example, can you blame the healthcare system in the U.S. for our higher-than-average rate of gun violence deaths? Is the healthcare system to blame for our comparably high infant mortality rate, or does the obesity rate and health status of expectant mothers have something to do with it? You see, when it comes to measuring the quality of a healthcare system, it’s very easy to offend everyone! Our social and lifestyle choices are sensitive political topics, so it becomes easy to default to life expectancy as a measure and to blame the healthcare system for the result.

I believe the assumption that shorter life expectancy has a direct correlation to the quality of the doctors, nurses, hospitals, technology, and training is far from truth. My mother is a three-time cancer survivor and the first woman in three generations on this side of our family to live through her early 40s because of the toll cancer has taken. The world-class care she received first at Baylor University Medical Center and later at UT Southwestern Medical Center, combined with the spirit of a fighter, have allowed her to see children and grandchildren get married.

Mick Jagger, the lead singer of the Rolling Stones, has the economic means to get care anywhere in the world. He had heart surgery in early 2019 at Presbyterian Hospital in New York. If the United Kingdom’s hospitals and doctors are so much better, then why in the world would he choose to seek care in New York? The reason Mick Jagger and many others choose to seek care in the U.S. is because, in many measures, we have the best hospitals, doctors, and nurses in the world. If this is the case, however, then how do we have the worst-ranked healthcare system performance?

Commonwealth Fund Rankings

The Commonwealth Fund has taken up the challenge and compared healthcare systems in 11 economically developed countries. The measurement includes five categories — care process, access, administrative efficiency, equity, and healthcare outcomes. The U.S. was rated as the best performer in many healthcare areas. Providers do a better job talking to patients about diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol risks. Specialists talked to patients about treatment choices and involved patients in decisions. Thankfully, the U.S. 5-year breast-cancer-survival rate was the highest.

Unfortunately, the U.S. was also the worst performer in many important areas. Americans had more cost-related access problems. Patients were more frequently surprised that things were not covered by insurance. Fewer Americans have a regular doctor, and the variance by income level for those who have a regular doctor is higher than other countries. The U.S. infant mortality was the highest, and the life expectancy at age sixty was the lowest. More Americans have at least two chronic medical conditions.

The bottom line is that the U.S. healthcare system ranked last among the 11 countries overall in access, equity, and healthcare outcomes. Our system is difficult to access and navigate, it’s economically biased, and the result is Americans often don’t get the care they need.

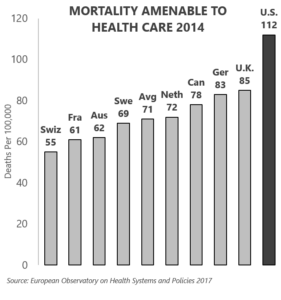

It’s difficult to find pride in the last-place ranking of these important topics. Of particular concern, is the last-place ranking in mortality amenable to health. An amenable mortality cause is one for which early detection or effective treatment could have prevented death. Translating this in a way my Texas public-school-educated mind can interpret, mortality amenable to health measures the rate at which people die from conditions that could have been discovered and effectively treated within the healthcare system. In other words, the diagnosis and treatment were available, but people died anyway.

The U.S. produced the most deaths per 100,000 people from factors amenable to healthcare — 59 percent above the European average. Our healthcare system failed to keep people alive from conditions that should have been treatable.

The T. Rex Effect

Except in the movies, the tyrannosaurus rex is long extinct. Imagine if there had been a cure available for whatever caused its demise. I call this lack of access to an available cure the “T. rex effect.” In the T. rex effect, a cure is available, but it’s just slightly out of reach. In my imaginary “dinosaur survival button” story, a button is high on a wall, or a tree, in our prehistoric example. A tyrannosaurus rex, with its awkwardly short arms, is unable to reach the button. Ultimately, the individual dinosaur dies, and its entire species becomes extinct because salvation, although available, was just out of reach.

Healthcare in the U.S. suffers from the T. rex effect. In many ways, we have the best healthcare system in the world, with some of the best physicians working in some of the best facilities, using some of the best technology and equipment in the world. In spite of the great doctors, hospitals, and technology, however, people in the U.S. die at a rate that’s more than 50 percent higher than the average for other economically developed countries. Our worst-performing ranking isn’t because the world’s best care is not available in the U.S. It’s because access to this care lies slightly out of reach for many because of cost, complexity, education, or other solvable factors. The right answer to our healthcare reform question is the one that removes cost and complexity hurdles to connect at-risk individuals to the care they need.

Do you agree? I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

And, be sure to tune in next week where I’ll take a look at more issues impacting our healthcare system. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to sign up for our “Insiders’ Club” where you’ll be notified when I release new information AND receive a FREE copy of my book “The Voter’s Guide to Healthcare: A non-partisan, candid, and relevant look at politics and healthcare in America” when it’s available.